Wilderness Plots

Praise for Wilderness Plots: Tales about the Settlement of the American Land

It would be difficult to find richer, more concise prose than that employed by Scott Sanders in this collection. ... Most of these tales resonate with the force of fine lyric poetry, and they come together beautifully to project aspects of the epic--an American epic. ... [Wilderness Plots] is a stunning achievement. --The Georgia Review

Sanders's skillful writing makes these Ohio Valley pioneers come alive. He has written vignettes of two or three pages each about the odd and memorable people and incidents that were talked about for years; the sort of thing that never seems to find its way into history volumes with any regularity. ... This is one of the best books of folk history around. --Sacramento (California) Bee

The language of these tales is chiseled, spare to the point of folklore: every word carries a lovely weight. ... Seldom has America's early story been so beautifully told. ... The book should appeal to anyone interested in Americana. It almost demands rereading: some may find its cumulative effect similar to that of Edgar Lee Masters's Spoon River Anthology. --Publishers' Weekly

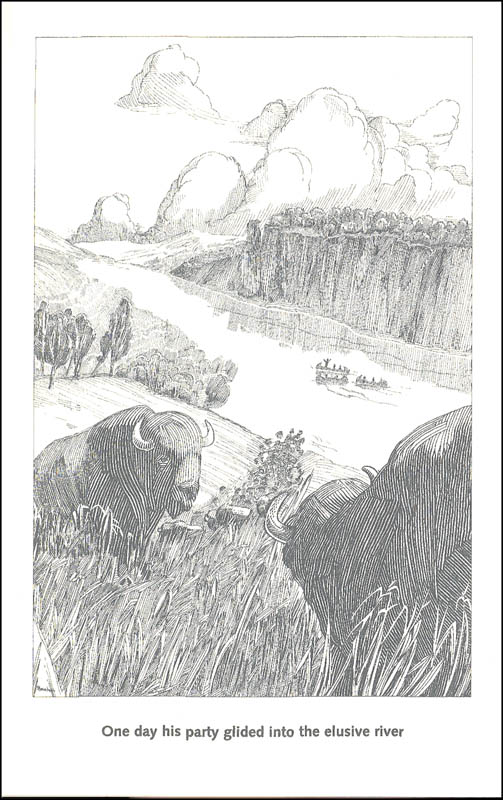

With illustrations by Dennis Meehan

FINDING THE PLACE

It cost Robert de La Salle $2,800 to discover the Ohio River. The Indians already knew where it was. “You do not want to go there,” they told La Salle. “There are monsters in those waters ready to swallow you and your seven canoes. The wicked men who dwell on those shores will pull the arms from your body and suck the marrow from your bones.”

La Salle had already sold everything but his coat and boots to finance the journey, so he was not going to be scared off by one tribe of savages warning him against another tribe. He took along two dozen men and three dozen muskets and a pair of priests. They paddled up the St. Lawrence, across Lake Ontario, and put in at a Seneca village near the mouth of the Genesee River. Having learned several Indian dialects in the leisure hours of his old trading-post days, La Salle was able to converse freely with his Seneca hosts. Do you know the great river to the west, he inquired, the one leading to the Sea of California and thence to China and Japan? They knew the great river that pours into the sea, yes. Would they lead him there? No, they answered, not for an armful of blankets.

After a month of fruitless hunting for guides, La Salle stumbled upon an Iroquois colony at the head of Lake Ontario. There he found a Shawnee prisoner who told him he could reach the great river in six weeks. Only six weeks? Fame was so close he could almost smell it. Eventually he turned up an Onondaga brave who was foolhardy enough to lead him.

By way of swamps, portages, and half the creeks in the territory, La Salle persevered in his journey to China. One day his party glided into the elusive river. Nothing in France could touch it for grandeur. In some places, herds of buffalo grazed in meadows that swept right down to the water. Brilliant green birds stitched the air with their singing. After weeks of paddling, there was still no sign of the California Sea, let alone China. The falls at Louisville finally turned La Salle back, in 1669. He was not quite sure what he had discovered, nor where it led, nor what it was worth. But it was a considerable river. Oyo, he called it, garbling the Iroquoian word: Oyo, Ohio, beautiful river.